James Thomson of Tanhill - A Covenanter Martyr

James Thomson was a forebear of Jean Tudhop (born 1788), wife

of James Harvie and mother of James Harvey (born 1826) who

emigrated to Tasmania in 1859.

This fascinating article describes the times and the role James

Thomson played. It has been abridged from the web site,

The Covenanters -

The Fifty Years Struggle 1638-1688 and has been enhanced by other information.

The Fifty Years Struggle 1638-1688

Introduction

This chapter of history is surprisingly unknown and undocumented outside the borders of Scotland. However it was a violent period that pitted fellow countrymen against each-other, rather like the English Civil War that took place around the same time. Although on a smaller scale it was often more brutal as the following chapters will describe:

Today South West Scotland is peaceful and largely prosperous. However there survive a large number of 'martyrs' graves, which are reminders of an altogether more turbulent past. Many are located on remote moorland, marking the spot where the King’s soldiers killed supporters of the Covenant. Others are to be found in parish Kirkyards either erected at the time or often replaced by modern memorials. Almost every corner of southern Scotland has a tale to tell of the years of persecution, from remote and ruinous shepherds' houses where secret meetings were held to castles and country houses commandeered by government troops in their quest to capture and punish those who refused to adhere to the King's religious demands.

Scotland was in an almost constant state of civil unrest because people refused to accept the royal decree that King Charles was head of the church (known as the 'Kirk'). When those who refused signed a covenant which stated that only Jesus Christ could command such a position, they were effectively signing their own death warrant. This was a grim period of religious persecution which witnessed the bloodiest crimes of the nation's history, committed by Scots against Scots.

The Scots holding their young kings nose to the grindstone

Origins of the struggle

James VI of Scotland became James I of England in March 1603 when he was declared rightful heir upon the death of Queen Elizabeth I. It is important to remember that during the reign of James as King of both Scotland and England, the two nations retained their separate parliaments and privy councils. Scotland passed its own laws and enjoyed its own law courts. Scotland had its own national church, its own taxes and trade regulations, and to a certain extent, it could pursue an independent foreign policy.

Scotland itself was practically two distinct nations. There was a huge division between Highland and Lowland. James's attempts to persuade the clan chiefs to adopt the Protestant faith were a failure. They clung to the military habits of their ancestors, their Jacobite (Catholic) heritage and continued the Gaelic tongue when most of Scotland had abandoned it in favour of English. James also had a long-running quarrel with the Presbyterian Scottish Kirk (a strict form of Protestantism) and resented what he saw as their interference in matters of state.

Presbyterianism as practiced by the Scots was a hard, unyielding faith. It was deeply suspicious of Christmas, and abominated graven images such as the crucifix. It did not recognise Easter as a celebration. James insisted that his divine authority came before the Kirk's civil jurisdiction. This conflict between two uncompromising factions was to strongly influence this whole period of Scottish history. James, despite his Scots ancestry, left London to visit his native country only once in the years he held the 'two crowns' between 1603 and 1625.

On the accession his to the throne in 1625, Charles I was determined to continue the work of his father. Charles proposed to bring the Scots church into line with that of England, an extremely controversial move which provoked outrage north of the border. He was an opponent of Presbyterianism and thought it would be simpler if all his subjects would adopt Episcopacy (government of the church by crown appointed Bishops).

He therefore planned the introduction of the 'Book of Common Prayer' into the Scottish church service. This took some time to plan and it was not until 23rd July 1637 that the new liturgy, which many Scots believed to be more Catholic than Protestant, was ordered to be read in the Church of St. Giles in Edinburgh.

Tradition has it when the new service was read, one worshipper, Jenny Geddes stood up and threw her stool at the Dean's head shouting out "Wha daur say mass in ma lug". The congregation erupted and the service had to be abandoned. Although this act is commonly portrayed as a spontaneous outbreak of popular indignation, there is evidence that the incident was carefully planned and contrived.

On 28th February 1638 the 'National Covenant' was produced on behalf of the Church of Scotland, backed by the nobility and gentry, in opposition to the new book of prayer. This was essentially an anti-Papist declaration and 60,000 folk gathered to sign the documents which had been placed on public display in Greyfriars church, Edinburgh. Other copies were taken throughout the country for further signatures, bringing the Scottish Kirk into direct conflict with the King and the rule of law.

Book of Common Prayer Charles 1 1625 - 1649 Solemn League of Covenant

Solemn League and Covenant

In 1643 Charles was ousted from the throne during a bloody Civil War by the English parliamentarians and Oliver Cromwell was installed as Lord Protector. One of his first tasks was to execute the King by beheading. The English Parliamentarians agreed that Presbyterianism be adopted as the national religion throughout England and Scotland as they were anxious to have the Scots allied against the still dangerous forces of the Crown. The Covenanters therefore sided with Cromwell and a period of stability ensued. The treaty between the two was called the "Solemn League and Covenant". This was essentially a marriage of convenience.

Scotland was now under English rule and the Church of Scotland enjoyed a time of spiritual prosperity. Cromwell was supreme lord of a united Britain which was now a conquered country living under an army of occupation. However the subjugation was to be short-lived as Cromwell died in 1658 and in May 1660 Charles' son, Charles II was fully restored to the throne. He soon passed an act which enforced the people to recognise him as the supreme authority in matters both Civil and Ecclesiastical. The Church of Scotland rejected this and was thrown into the furnace of persecution for twenty eight long years until 1688.

Repudiation of the Covenant and Rullion Green

In 1661 the National Covenant was repudiated by Charles II. The following year the Covenant was torn up and Charles' own Bishops and curates were appointed to govern the churches and 400 non-conforming ministers were ejected from their parishes. At first the authorities tolerated them preaching in houses, barns or the open-air, but it was soon realised that the people's resolve was such that they would not attend the government-appointed Episcopal minister's services. The first attempts at limiting attendance at these conventicles were made in 1663 and, by 1670, attendance had become treasonable and preaching at them, a capital offence.

By 1666 the persecution by soldiers given lists by the curates of the names of the non-attendees at church, was so bad that the country became increasingly restless. When the village of Dalry in Galloway witnessed an old man being roasted with branding irons by the soldiers, a rebellion commenced. It had not been planned, but numbers flocked to the cause and a spontaneous march took place in horrific November weather across Lanark towards Edinburgh. The exhausted Covenanters were ultimately defeated at Rullion Green in the Pentland Hills when an army of 3,000 led by General Tam Dalyell routed the meagre band of 900 protestors. 100 were killed on the battlefield and 120 taken prisoner and marched to Edinburgh and charged with treason and rebellion. It is estimated that a further 300 Covenanters escaped, but they died or were slain on their way home.

The captured Covenanters were crowded into part of the High Kirk in Edinburgh known as 'Haddock's Hole'. They were brought before the Justiciary Court and on December 7th 1666 they were found guilty and sentenced to be hanged on the Mercat Cross in Edinburgh. As many as ten Covenanters at a time were despatched on the one scaffold. Their bodies were dismembered and the pieces exhibited in the Covenanter's own locality as a warning to others.

Conventicles

On 13th August 1670 the government declared that conventicles, or meetings in the fields, illegal and it was a capital offence to attend. The authorities were concerned that these were becoming a hot-bed of revolutionary ideas. The vast outdoor assemblies were being thrilled by the preacher's words of fiery defiance and doom-laden prophecy. However the Presbyterians defied the government and held secret religious meetings in the hills, usually with a circle of lookouts, often armed, posted around the site to watch for approaching dragoons. There were many bloody skirmishes amongst the bare lowland landscape. This was a time of legends - of the soldiers throwing women in pits full of snakes for fun and of men being hanged on their own door lintels.

The directive was that all conventicles were to be broken up and any land owner who refused to help could be fined. Instead of turning master against man, it forged links of shared suffering. Secret conventicles were attended by thousands of people at only a few hours notice, with mass marriages being carried out with a rock as alter and baptisms performed in small streams. Followers of the Covenant were willing to risk the fines and sentences in order to hear the preachers. For example 7,000 people attended a conventicle near Maybole in Ayrshire in 1678, performed by four ministers and at East Nisbet in Berwickshire the same year 3,200 took part of which 1,600 were seated. A massive conventicle took place on Skeoch Hill in Kirkudbrightshire in 1679. There were 6,000 Covenanters in attendance to hear three preachers, of which 3,000 were allowed to take part in communion. In the centre of the congregation a series of large boulders were arranged in four parallel rows for the communicants, perhaps around 300 at a time to sit on. These stones, known as the Communion Stones, are still there.

Often the conventicle was infiltrated by a few non-adherents who slipped off early to inform the authorities. The Covenanters had to be highly vigilant as the threat of armed intervention was ever present. The participants were most likely to be captured or executed, usually on their way to and from a conventicle. The fact that the citizens were away from home and probably had a bible in their possession was enough for the authorities to justify fining or executing them, often killing them where they stood.

Illegal conventicles were usually held in the open air

The "Highland Host"

The government were becoming desperate and in early 1678, nine thousand soldiers from the largely Catholic highlands were brought south from their garrison in Stirling to Glasgow and the south-west. The town fathers of Ayrshire wrote to the Earl of Lauderdale, a senior government official, requesting him not to send so "inhumane and barbarous a crew of spoilers" into that county. The appeal fell on deaf ears. Parties of highland soldiers were quartered on land owned by suspected Covenanter sympathisers and they were required to feed the soldiers and barrack them for nothing. These soldiers were known as the 'Highland host' and the highlanders were responsible for many atrocities including robbing their hosts of all belongings and livestock; of rape and of pillage. Thousands of pounds worth of damage and theft were done in the few months they were in the south-west.

One example was in Kilmarnock where nine highland soldiers were quartered with William Dickie for six weeks. He was required to supply them with food and drink and, when they eventually left his house, they stole bags full of ornaments, cutlery, plates and a sock full of money, to a total value of 1,000 merks (Scottish £’s). The soldiers also maltreated him and his family. His wife was pregnant, yet one of the highlanders stuck a dirk (knife) into her side and she died soon after. Dickie himself was struck on a number of occasions for not supplying all the soldiers’ needs and one of the beatings resulted in two broken ribs.

The minister of Kilmarnock, Rev Alexander Wedderburn, was so appalled by the actions of the highlanders in the town that he condemned them in one of his sermons. The highlanders heard this and caught up with him as he walked through the streets. In a scuffle one of the soldiers lunged at the minister with the butt of his gun, winding him and causing him to fall to the ground. He died shortly after of respiratory disease.

Many parishes have records which detail the cost of putting up the highlanders, sums in money which were long in recouping. For example, two hundred and fifty soldiers and officers from Caithness were quartered within the Parish of Cumnock for fifteen nights and the total losses recorded in the accounts were £3,015 6s 8d. The total for Avondale parish in Lanarkshire was reckoned to be £1,700, although it has been surmised that this figure was only one third of the true total.

Battles of Drumclog and Bothwell Bridge

The situation was becoming grave in the Lowlands and South West and by 1679 the men of Galloway were to rise again in what became known as the 'Second Resistance'. It began with the "Rutherglen Declaration" when they condemned the proceedings of the government since 1660. Shortly afterwards a huge conventicle was arranged, somewhere in Lanarkshire. This was more than a gesture of defiance; it was a challenge the government had to meet to retain their credibility.

John Grahame of Claverhouse[1], known to his enemies as "Bloody Grahame," rode out from Glasgow with about 180 dragoons to deal with them. Born in 1648, near Dundee, he was abhorred by the Covenanters for the part he played in ordering the execution of many friends and supporters, many being killed by his own hands.

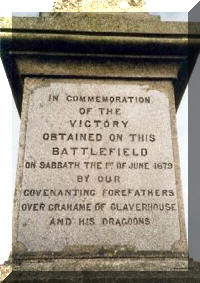

He found them drawn up in order of battle at the farm of Drumclog, near Loudoun Hill, on the morning of 1st June 1679. They had chosen their position skilfully, in front was a deep ditch and all around were bogs. As the women and children were sent to the rear, the men moved forward. Under the command of Sir Robert Hamilton, there were about fifty men on horseback, and two-hundred foot. Some had swords and firearms; the rest had homemade pikes, halberds and pitchforks. John Balfour of Burleigh and David Hackston of Rathilet, who had participated in the recent murder of James Sharp, Archbishop of St. Andrews, were both there, acting as officers, as was William Cleland, a young man who was later to become a famous soldier as the first colonel of the Cameronians, was given a command in the foot. The Covenanters had had little fear of the scarlet soldiers coming towards them on horseback.

Rather than wait for reinforcements from Glasgow, Claverhouse decided to risk an engagement even though he was unfamiliar with the terrain. His confidence that his men were dealing with no more than a badly armed rabble clearly outweighed his judgement. He sent a skirmishing party out towards the moss. In response the conventanters sent forward a party of equal size under Cleland, which advanced to within pistol shot of the enemy. As the government soldiers raised their carbines to fire, the rebels immediately prostrated themselves on the suggestion of Burleigh, with the exception of one John Morton who, taking a rather strict view of predestination, refused to stoop, and was killed instantly.

After the exchange of musket fire with little effect, Claverhouse held back as he had no-one to guide his men through the morass. His enemies solved his problems for him. Led by Cleland, a large party of men made their way around the ditch and threw themselves on the dragoons who by now had dismounted. With a cry of 'over the bog and on them lads' they moved forward to engage the dragoons in close quarter combat with halberds and pitchforks. Unable to form proper ranks, the dragoons who were bogged down in the marshy ground and totally outnumbered, now found themselves in serious difficulties. Thirty six dragoons were killed in the battle compared to the two battlefield conventanter casualties, seven dragons made prisoner and the rest fled towards Strathaven. Claverhouse went down in history as losing the battle of Drumclog.

Following this victory, the Convenanters thought their time had come and proposed to march on Glasgow. As they started the march, they discovered that fearful residents had placed barricades across the streets to prevent them from entering the city. It was now full scale civil war, with the militia mobilised and armed men guarding the fords over the River Forth on the approaches to Edinburgh. The Covenanters turned about and at Bothwell Bridge, a crossing over the River Clyde just north of Hamilton they made their stand. By now they had become a rabble with no military formation.

This time they were soundly defeated by government troops led by the Duke of Monmouth, with perhaps 600 killed on the field and 1,200 taken prisoner in the subsequent pursuit. Most of these were marched to Edinburgh where they were locked up in an enclosure of Greyfriars Kirkyard. Five months later after many had escaped, some had died and others were forced to sign a declaration of government support, 257 Covenanters remained. They were sentenced to banishment to the American plantations and placed on board a ship at Leith. However it foundered off the Orkney Islands in the far north of Scotland, with almost all on board being drowned.

John Grahame of Claverhouse Monument at Drumclog Inscription on Drumclog monument

James Thomson of Tanhill

James Thomson, born about 1630, was a farmer from Tanhill which is on the west side of Lesmahagow parish, bordering Stonehouse. The family of the martyr was in earlier times located in a place called Cunningair or Collingair in Stonehouse parish opposite Dovesdale. The Thomson family is said to have departed Tanhill around 1780[2], having been tenants of Tanhill for near 350 years. Mary Thomson, mother of Jean Tudhope, who was in turn the mother of James Harvey who emigrated to Tasmania in 1859 was a great great granddaughter of the martry.

Little is known of this martyr, except that he died from wounds inflicted at the Battle of Drumclog in 1679, aged 49. His wife and son, John Thomson (great grandfather of Mary and born in 1655), were imprisoned in the Castle of Blackness, Falkirk, in Linlithgow which was, at that time, the principal state prison in Scotland. John, recently married to Helen Miller (born 1658) who was pregnant with James (Mary’s grandfather), may have spent some time imprisoned, as he and Helen did not have another child until 1692. What happened to James’ wife is unknown.

James’ body was later interred in St.Ninian's old kirkyard at Stonehouse. His tomb is known locally as the Bloodstone or 'Bloodstane'. The headstone reads:

Here lays or near this Ja ThomsonWho

was shot in Rencounter at Drumclog, June 1st 1679

By bloody

Grahame of Clavers House

for his adherence to the Word of God

and Scotland's

Covenanted Work of reformation - Rev xii 11

On the other side :

This hero brave who doth lye here

In truth's defence did he appear,

And to Christ's cause he

firmly stood

Until he'd sealed it with his blood.

With

sword in hand upon the field

He lost his life, yet did not

yield.

His days did End in Great renown,

And he obtained

the Martyrs Crown.

The following extract from ‘Wha’s like us?’ by a local Stonehouse historian John R Young, tells the eerie tale of the headstone and its unusual name.

“Told to me many years ago, I neither believed the story, nor found evidence of its existence, until of late. As a child I had been told of a gravestone in the old cemetery with a hole in it, whereby inserting ones finger in this hole, it was said to come out covered in blood! I dispelled this as a myth until out walking one summer day in the cemetery. To my amazement and, by sheer coincidence, I found the said hole in a headstone, more commonly known as the Covenanters’ stone. The hole is located on top of the headstone, directly below the mouth of a carved skull. When I found the headstone I immediately remembered the tale told to me as a boy and hesitantly stuck my finger into the hole. Pulling out my finger, it was indeed red, not with blood but with red ochre dust. This is due to a vein of red ochre running through the sandstone within the headstone. When raining, however, the red ochre could give the impression of ‘blood’ to the younger and more imaginative mind.”

His descendants renewed his headstone in 1832 and it was repaired again in 1955 due to damage caused by the elements. His descendants, including many in Stonehouse, are numerous and many of them have been elders in the Presbyterian Church of Scotland.

The "Killing Times"

The period from 1680 until 1685 was one of the fiercest in terms of persecution and a few months between 1684-5 became forever known as the "Killing Times". Charles' brother James II came to the throne as a believer in the Devine Right of Kings and a supporter of the Roman Catholic faith. It became his sworn intent to totally eradicate the Presbyterians.

Parish Lists were drawn up in accordance with instructions to the Episcopalian Curates to furnish Nominal Rolls of all persons, male and female, over the age of 12 within their Parishes. The Ministers were ordered to give "a full and complete Roll of all within the Parish" and "that to their Knowledge they give Account of all Disorders and Rebellions, and who are guilty of them, Heritors or others." Their instructions concluded, "No remarks need be made upon these Demands made upon every Curate in every Parish; they are plain enough, as also their Desig." The 'design' of this census was obviously to assist in the control and persecution of the Covenanters. The list drawn up for Wigtownshire in 1684 featured a total of 9,276 individuals in the 19 Parishes and was probably ordered by John Grahame of Claverhouse, who had been appointed the Sheriff of Wigtownshire.

These were the most horrific and atrocious times ever inflicted on the people of Scotland. The Covenanters were now flushed out and hunted down as never before and the common soldier was empowered to take life of any suspect at will, without trial by law. The persecution was done without any evidence and often as the result of the suspicions of an over-zealous town official or Minister. Brutality in these days defied the imagination and there was no mercy for any man, woman or child, irrespective of circumstances. Any Covenanter, once caught by the King's troops, was shot or murdered on the spot. They were usually buried on the spot because if the body was buried in a Kirkyard, it could result in another death. If the authorities learnt that a murdered Covenanter had been given a decent burial, their bodies were usually disinterred and buried in places reserved in places for thieves and malcontents. Quite often the corpse was hanged or beheaded first.

The following are some examples of events of the time.

The Murder of John Brown

Most of the well-known martyrdoms took place at this time, including the notorious murder of John Brown by Claverhouse at Priesthill, about one mile from the Strathaven road. His martyrdom was at his own front door, in full view of his wife and children after a long chase through the moors and mosses of Lanarkshire and Ayrshire. John was a devout Christian and would probably have been a fierce preacher were it not for the fact he had a speech impediment. Many Covenanters were welcomed to his cottage and illegal meetings were held there. On 1st May 1685 a number of soldiers arrived, commanded by John Grahame. Brown was asked to swear the oath of allegiance to the crown, but he refused. It was noted that in his answers to Grahame, Brown's stutter left him and he is said to have responded with the eloquence of a preacher.

He was then dragged back to his own front door and in front of his daughter and wife Isabel who had their baby boy in her arm, he was thrown to the ground and told to pray. Claverhouse's temper grew as the prayers went on and on. He interrupted Brown three times and bellowed that he "gave him time to pray, not preach". 'Bloody Grahame' then ordered his men to shoot the Covenanter and it was reported that they initially hesitated, as they were to perform the act in front of women and children. It is said that Claverhouse suffered nightmares afterwards and the words of Brown's prayers continually haunted him. Friends helped Isabel to bury her husband near to where he fell and the spot is still marked with a memorial and flat gravestone. Many of Brown's descendants still live in the surrounding towns of Lanarkshire.

Who will hang them?

At Ayr there is a headstone to seven martyrs who were executed in the town as a warning to the townspeople of what would happen if they joined in any of the uprisings. The men were not of the county but were brought there and hanged as an example, the same happening in Dumfries and elsewhere. There were originally eight men to be hanged, but the burgh hangman disappeared, and the hangman brought from Irvine refused to do it, even under threat of torture. Therefore the authorities announced that one of the men could go free if he agreed to hang the remaining seven. Cornelius Anderson agreed, only if his associates would offer him forgiveness. Forgiveness was forthcoming, and following the execution Anderson emigrated to Ireland, where he died insane.

Killing at Blackwood Farm

In April 1685, a group of 12 Covenanters including James White formed a small prayer group at Little Blackwood farm, near to Moscow in the parish of Kilmarnock. Peter Inglis was in charge of a company of troopers, based at the garrison in the keep in the small town of Newmilns. He had heard that an illegal covenant was planned, so he set off with a small group of soldiers. On reaching the farm they split up and surrounded the building. Something disturbed the meeting inside, perhaps a dog barking. In any case, the Covenanters abruptly ended their meeting and tried to make their escape. As they stumbled about in the darkness, the Dragoons loosed a volley of shots at White and he crashed to the ground dead. Of the others eight were apprehended and three managed to escape.

Peter Inglis found an axe on the farm and instantly severed White's head from his body. Grabbing it by the hair he tied it to his horse's saddle and returned with his trophy to Newmilns. The remainder of White's body was left lying on the ground and was trampled by cattle which were stolen from the farm. His remains were later interred at Fenwick. The captured Covenanters were arrested and marched to the garrison at Newmilns. The following day the word had spread throughout the Loudoun area about the incident and a crowd had gathered close to the garrison. They were shocked and repulsed to see Inglis carry out White's head by the hair and on the burgh green threw it into the air. When it landed the soldiers and he kicked it around, playing a makeshift game of football.

The next morning Captain John Inglis, Peter's father, was about to execute the eight prisoners when officials of the burgh intervened and stated that an official order should be obtained. Peter Inglis was then despatched to Edinburgh where he readily received such an order from the Privy Council. However the parishioners of Loudoun were planning a rescue that night to spring the prisoners. A group of about 60 men approached the tower and easily overpowered the guards. In the ensuing scramble two soldiers were shot. Using large hammers they had borrowed from the local smithy, the rescuers battered the gate down and all were able to escape. The only casualty in the mêlée was John Law, one of the rescuers shot by a soldier from an upper window in the tower. He was buried where he fell in the castle yard.The soldiers searched the district the following day, but had difficulty in recapturing the prisoners. They discovered a man named James Smith at East Threepwood Farm near Galston, who had given the fugitives some food. He tried to escape, but was wounded by soldiers at his front door. He was taken to Mauchline Castle where he later died of his wounds.

James Renwick

In 1688, the fugitive preacher James Renwick was captured an executed at the scaffold in Edinburgh's Grassmarket, the last Covenanter to suffer a public execution. He was born in Moniaive in Dumfriesshire on 15th February 1662, the son of a weaver, Andrew Renwick. He was always interested in religion and it is said that, by the age of six was able to read and question the contents of a bible. His parents scrimped and saved to ensure James received an education and after attending school in Edinburgh was able to attend the University. After graduating with an MA degree in 1681, he began to question the King's authority over the church after witnessing the public hanging of a number of Covenanters. He moved to Lanark and started to attend a series of conventicles and in October 1682 was chosen to study for the ministry at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands. He was ordained in May 1683 and arrived back in his homeland in October that year. On 23rd November 1683 a large conventicle was held at Darmead at which he commenced his ministry, preaching to hundreds of people.

Thus began one of many close shaves with the authorities. In July 1684 he was travelling with three others across Strathaven Moor. They were spotted by Dragoons and a chase ensued. He galloped towards the summit of Dungavel Hill, dismounted and hid in a hollow until nightfall before he moved on. In the next few months he was responsible for the baptism of over 300 children and also performed many marriages and funerals, all held in remote farms and on the moors.

In September 1684, the Privy Council had issued a warrant for his capture and the following year Renwick was at the head of 200 Covenanters who affixed a declaration on the cross at Sanquhar, in which James VII was denounced as a murderer an idolater. After this he made sure there was a lookout stationed wherever he went and at any conventicle at which he was preaching and there was always a horse standing by, saddled and bridled, on which the fugitive could make a swift getaway. His last conventicle took part at Riskenhope in Selkirkshire in January 1688. According to an onlooker, James Hogg, "When he prayed that day, few of his hearer's cheeks were dry. My parents were well acquainted with a woman whom he there baptized". Renwick was apprehended on 1st February 1688 on one of his secret visits to Edinburgh. A group of excise men visited the home of his friend and trader John Lackup under the guise that they were checking up on him. In reality they were hoping to capture Renwick and claim a reward. A scuffle broke out and the preacher made a bid for freedom, running down the Castle Wynd. However he was easily caught, taking a number of blows in the process and then taken to gaol. Patrick Grahame, Captain of the Guards, looked at the 26 year old and asked "Is this boy the Mr Renwick that the nation hath been so much troubled with?

Placed on trial, the witnesses for the prosecution included such notables as Claverhouse himself. He was sentenced to die on 8th February 1688 and the execution was postponed for two weeks. In which time Renwick received numerous visitors including the Bishop of Edinburgh and the Lord Advocate who pleaded with him to accept at least some rule of the King, but he refused. On the day of his hanging he was allowed to see his mother and sister who had made their way up from Dumfriesshire, his father having died when James was twelve.

On the scaffold Renwick attempted to address the crowd, but all the time the soldiers beat their drums in order to drown out his words. The hangman sprung the trapdoor and he dropped to his death. His remains were taken from the scaffold by a follower and rolled in a winding sheet before being buried in Greyfriars' Kirkyard. Renwick would have been the last Covenanting martyr but for a 16-year-old lad, George Wood. He was shot down in the fields a few days later near the village of Sorn, Ayrshire and is buried in the parish Kirkyard there.

Renwick being taken to his execution

The "Glorious Revolution"

However for the Covenanters the period of terror was nearly over. For all his provocative attempts to restore Catholicism in England, King James II still had powerful support among the Tory stalwarts of the established order. But he seemed bent on undermining his own power base. In the spring of 1688 he ordered his Declaration of Indulgence, suspending the penal laws against Catholics, to be read from every Anglican pulpit in the land. The Church of England and its staunchest supporters, the peers and gentry, were outraged. The birth of an heir, James Francis Stuart (later to become the Old Pretender) increased public disquiet about a Catholic dynasty; fears confirmed when the baby was baptised into the Roman faith.

At the end of June a small group of peers made the fateful decision to invite William of Orange, James's son-in-law, to "defend the liberties of England". William prepared carefully, assembling a formidable army of multinational mercenaries in Holland. In November he landed at Torbay, at the head of 15,000 men. Cleverly, he made no public claim to the crown, saying only that he had come to England to save Protestantism. James, meanwhile, marched west with his small but well trained army. But to his dismay he found his troops deeply discontented and unwilling to fight.

At Salisbury there were mass desertions, and the king turned tail for London. Even then, James had hopes of retaining his throne, but his nerve failed him. He made for the Kent coast, was turned back by magistrates at Faversham, and was forced to sail from London. Finally, on Christmas Day 1688, he landed in France and from there he moved onto Ireland. William moved swiftly to neutralise the royal army and establish a provisional government. In January 1689 a hastily summoned Parliament declared the throne vacant. In February William and Mary - the daughter of King James - jointly acceded. The second English revolution of the century had been accomplished without violence.

This put an end to the House of Stewart which had ruled over Scotland for over 300 years and England, Scotland and Ireland for eighty six years. James and his son Charles tried to reclaim the crown in the Jacobite risings of 1689, 1715 and 1745, but were unsuccessful. The ''Glorious Revolution" had taken place and the William, the new King was persuaded by his advisors, principally William Carstares, a Scottish minister who had become a friend of William in Holland to accept Presbyterianism as the established church in Scotland. In the year 1690, therefore Parliament met and passed an act which re-established Presbyterianism in Scotland and to this day the Church of Scotland remains a Presbyterian Church.

The House of Stewart had maintained they had been appointed kings by God and not by the people, but in dethroning James the people had claimed the right to appoint their own kings. For this time onwards, therefore, it came to be understood that kings would be allowed to remain on the throne only if they governed according to the laws of the land. After the revolution the kings could make no changes in the laws without the consent of the Parliament. Thus after James was dethroned a new day dawned, both in England and Scotland.

Summary

For 50 years the non-conformist Covenanters had been fined, tortured, flogged, branded or executed without trial for failing to turn up to hear the "King's Curates" in the pulpit. One famous observer of the times, Daniel Defoe, the author of "Robinson Crusoe" estimated that 18,000 had died for their adherence to the Covenant. Of those that lived, many had been sold as slaves to America or sent to the dungeons on Bass Rock or Dunottar Castle. Those who escaped sought refuge in Holland and England. Others were amongst the 100,000 Scots who emigrated to Ulster province in Ireland as part of the Ulster Plantation (of Protestants, displacing Catholics) that James I commenced in 1601, which created the cauldron which exploded as the “Troubles’ in Northern Ireland from August 1969 and ending in 1998.

The cause still rings out on many martyr graves scattered throughout the South West as follows: "For the word of God and Scotland's work of Reformation. Scotland's heritage comes at a price which invokes our greatest heartfelt thanks for the lives sacrificed on the anvil of persecution, when innocent blood stained the heather on our moors and ran down the gutters of our streets with sorrow and sighing beyond contemplation".

Kirkyards all over Scotland have tombstones to victims of the years of Covenanting persecution, but no area is as rich in them as the south-west corner of Scotland, particularly the counties of Ayr, Lanark, Kirkcudbright and Dumfries, where virtually every Parish Kirkyard contains at least one Covenanter's grave. Many more are to be seen on the moors and hills which the Covenanters were forced to frequent, the bodies of the shot hill-men being buried where they fell.

[1] John Grahame of Claverhouse was awarded the title of Viscount Dundee, and in 1689 he raised an army of highland men on behalf of James VII who was now in Ireland plotting a comeback. The rigid, intolerant government of the Presbyterians was not to the taste of the mainly Catholic highlanders. The establishment class were also horrified by the thought of the dethronement of the last in a line of at least 100 Scottish kings. The royalists marched on Killiecrankie in Perthshire, where a battle took place on 27th July.

Although "Bonnie Dundee's" forces numbered between 1,800 and 2,000 men, he was outnumbered by almost two to one by government troops. Nevertheless, his men were victorious in the battle against the soldiers under General McKay, who retreated across the River Garry, one of them famously leaping the rocky chasm. Claverhouse was mortally wounded by a gunshot and his body was stripped of armour and clothing. A soldier found the corpse the following day and, wrapping it in a plaid, took it to the kirk at Old Blair, near to Blair Atholl where it was buried. Despite the fact that the day belonged to the Jacobites, Bonnie Dundee's now leaderless uprising soon petered out into a series of minor skirmishes.

[2] From the article by John R Young on the Convenanters on the St Ninian’s, Stonehouse site (www.st-ninians-stonehouse.org.uk), “Our Church” and coincides with the death of most probably John Thomson in 1779, father of Mary Thomson, born in 1720 at Tanhill in 1779 aged 59 or improbably James, grandfather of Mary, aged 99. The Scobie web site states that the family arrived at Tanhill in the late 1500’s. Alasdair Malpas, son in law of Lord & Lady Manners of Hampshire and the “official” Thomson family historian, has the branch of the Thomson’s the Harvey’s are descendent from arriving in 1601 from Collingair in Stonehouse parish to take over the Tanhill from ‘the original’ branch. George Hamilton provided the above information and his web site has the 1601 Thomson’s name leap-frogging by the names John and James each alternative generation back in history as far back as 13th century, from Perth, Scotland.